Scene Composition

The scene contained within a panel is made up of all of the elements within it, including the characters, scenery, objects, speech bubbles, and sometimes even the frame itself. We have discussed when and how to describe speech bubbles and characters, and here we are going to provide an overview of how to describe the layout of the scene.

Left and Right

There are two ways we need to think about left and right. The first is from our point-of-view, in the context of the panel, and the second is from the point-of-view of the character.

In the context of the panel, it is often helpful for understanding the composition of the scene to say if someone/something is to the left or right of the panel. This will help the reader orientate themselves within the scene.

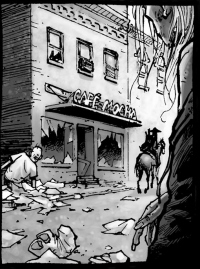

Pull out to a wide view of the street. The alleyway is to the far left of the frame. Rick and the horse are seen from behind, near the edge of the panel as they walk past the Café.

We use left and right as needed, but attempt to minimize their use in order to minimize confusion. Compare the two panel descriptions below - one is from one of our earliest drafts, and the other is from one of the most recent.

Early Version: Rick’s right foot is on the landing in front of the screen door, his left foot is on the step just below. His right arm is stretched out in front of him. To his left, a black mailbox with hooks for a newspaper is affixed to a brick wall. On the left is a broken window. The broken glass is scattered on the landing.

Current Version: Rick walks up the porch steps. The outer screen door is half-open.To his left, a black mailbox with hooks for a newspaper is affixed to a brick wall. On the left is a broken window. Broken glass is scattered on the landing.

We learned to be far more succinct in our descriptions, and this results in the information being conveyed more clearly.

The above example also showcases the left/right issue with respect to the point-of-view of the character. We do not usually need to specify which hand is doing an action, unless it is important in some way. Or, if you do describe what “the left hand” is doing, when you describe the right, just call it “the other hand”. For instance, if you say “His right arm is stretched out in front of him…” you can say”…and his other arm hangs at his side.”

Foreground / Midground / Background

An image can be broken into three main layers as viewed by an observer. These are the foreground, middle ground (aka midground), and background. The foreground is the closest layer of the image in the panel, and has the most details. It is the main focus of the panel. The middle ground, or midground, is considered the middle of the panel, where details are still in focus but slightly more vague. The background is the farthest layer of the image in the panel with the least amount of details and blurred colours.

Some guidelines are:

- Foreground: You will almost always describe what is in the foreground, but you do not always need to state it. A good example is when you have a panel that is a close-up of a character’s face - describing it as a close-up delivers sufficient information for the reader to accurately imagine the panel. (Note: there might be things in the midground or background, behind them, that you may need to clarify further.)

- Midground: You will almost always describe what is in the midground, and will need to state that it is in the midground if there are no further reference points. For example, in this panel we clearly state what is in the foreground, midground, and background.

- Background: The background is described often, and a good rule of thumb to remember is: if the background does not change from the previous panel, you probably don’t need to describe it again. To cut down on repetitiveness, you can also sometimes say things like “in the (far) distance…” to describe the background, instead of always saying “in the background.”

The following example is a panel where we clearly state what is in the foreground, midground, and background.

Wide panel.

Close view of Rick from the side. Rick is visible in profile.

In the background, framed by Rick’s hat and face, is a two story farm house with a side garage and front porch, deep back in a grassy field. It is surrounded by trees. In the midground the top of a wooden fence is just visible at the side of the highway.

Rick is in the foreground; he squints his eyes as he looks straight ahead. His jaw is set and his mouth is in a small frown.

But in the next panel that follows it, we do not need to be so precise, because the scene has been established.

Vertical panel.

Pull out slightly.

The shoulder of the highway is now visible in the foreground of the panel. The wooden fence is a few feet further back surrounded by tall grass. The house is still visible in the distance.

Rick’s face is in silhouette as he turns to look toward the house.

“Huh…” he wonders.